The art of cyber war with Isaac Porche

Porche shares the global state of cyber warfare, and how his time at Michigan led him to the front lines.

Enlarge

Enlarge

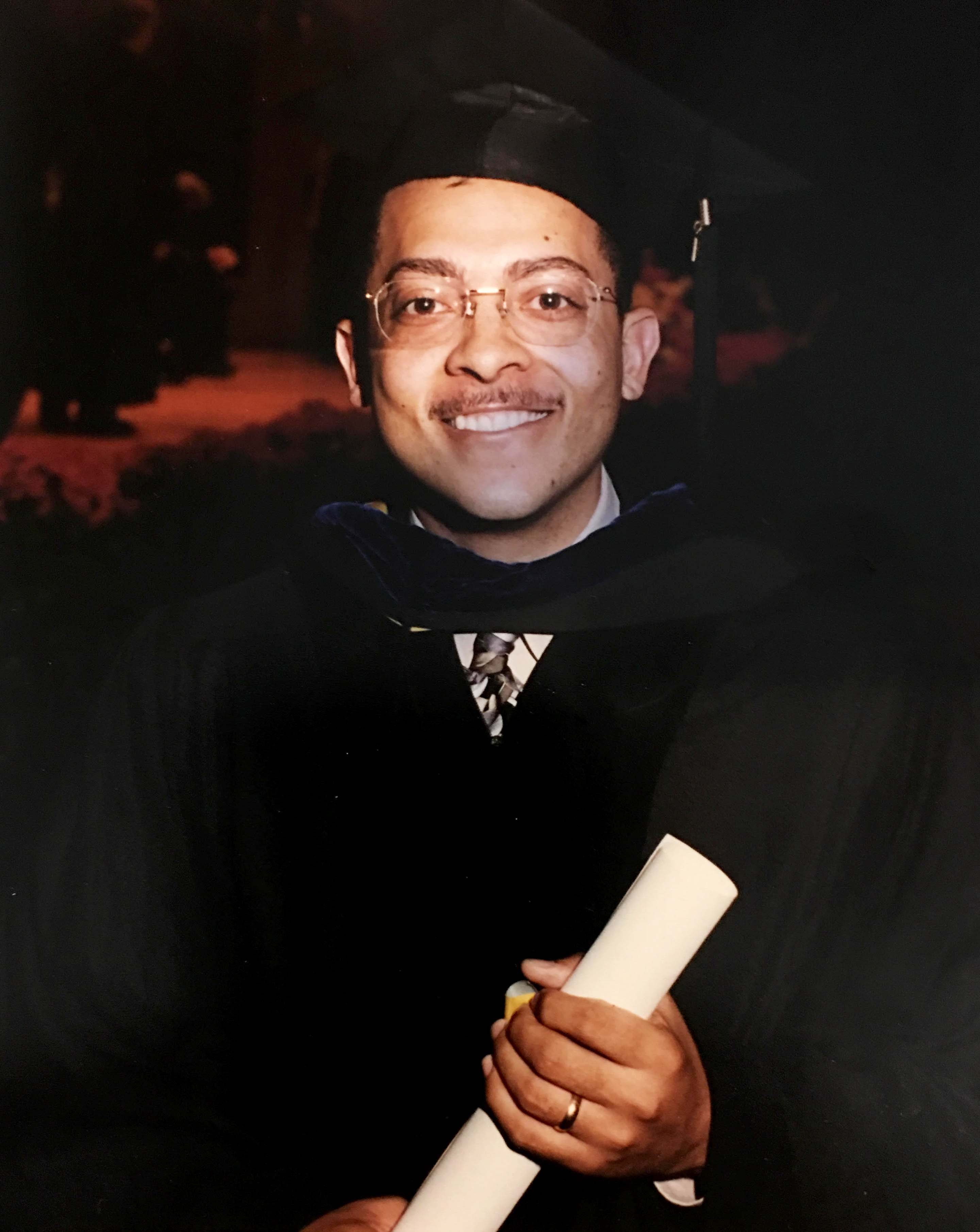

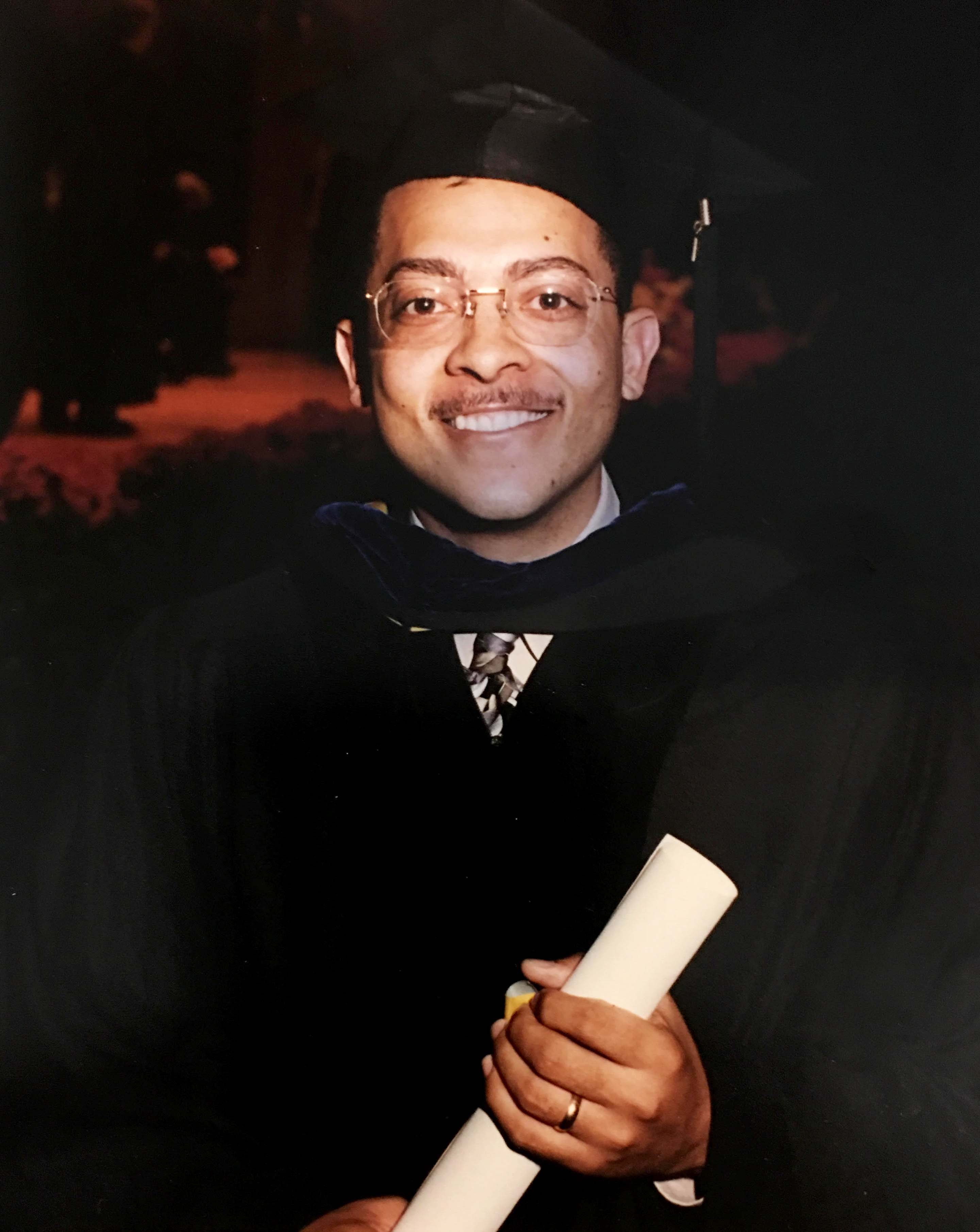

Isaac Porche (PhD EE:S 1998) is a senior engineer at the RAND Corporation, where he leads research to help Homeland Security and the government adopt proper cyber security tactics.

In this interview, he shares the global state of cyber warfare, the threats to government computer systems, and how his time at Michigan led him to being on the frontlines of technological attacks.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Louisiana and went to Southern University. My dad was on the faculty there. When I was a freshman, I won a General Motors scholarship, which would pay for my undergraduate degree and bring me to southeast Michigan every summer. I grew up as a GM guy, and that established my Michigan roots.

What brought you to the RAND Corporation?

I did a lot of modeling and simulation work in graduate school, including simulating traffic control systems. At one point, we were counting cars in Ann Arbor to feed into our model.

RAND was looking for people with model and simulation experience, and they hire a lot of PhDs to turn into principal investigators.

A lot of our government research is funded by the Army, the Navy, the Air Force and the Marines. They wanted models and simulations of combat. I developed models for communication devices that the Army would use, and I became a computer network expert.

How did your job evolve?

I started studying how networks would or would not help the war fighter.

That allowed me to transition from the modeling and simulation geek, which I was proud to be, to more of an information theory guy exploring what happens when soldiers are better connected. And that led me to studying the security of these networks.

This is around the time when cyberspace became an area of contention. A decade ago, we were asked if this was the computer geeks trying to convince us that they’re warriors, too. And the answer was yes.

Cyberspace was going to be an area of concern, both to protect yourself and your information, and an area of influence.

So, I became a cyber security and communications expert for the Army and the Navy. I started leading a bunch of studies and panels, and RAND eventually put me into management for the Army, and now, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Currently, we’re up to about $15M worth of studies and analysis, with about 20 principal investigators.

It’s a maturity of us as a civilization. We’ve decided you don’t have to lob missiles at people to change outcomes.

Isaac Porche

Where does the U.S. rank in terms of cyber security?

We’re behind when it comes to security, because it takes a long time to refresh big government systems. I was once touring a destroyer, and out of the corner of my eye I see a sailor changing this big giant tape drive. When they put IT systems on ships, they’re made to last 30 or more years. We even had ships running Windows 3.1 and Windows XP not long ago. You can imagine the insecurity of that.

The most important cyber warrior is the acquisition person, who must figure out how to get you new software and hardware when you discover that, yet again, your current system is inadequate.

Do you consider yourself part of a new type of cyber war?

I think cyber conflict is here, especially after the last election. It took the US a very long time to recognize that you can use social media to influence people. Eastern Europe saw it for years, Europe saw it for years, and it’s been in the doctrine of many countries.

It just took this election for people to say, “You know, people are going to try to influence American citizens, and it’s not just going to be the marketers.”

To some extent, it’s a maturity of us as a civilization. We’ve decided you don’t have to lob missiles at people to change outcomes. Most theorists who study war say war is a means to get to some political end. But if we can influence people around the world electronically, then there’s no need to park a ship outside a city or threaten to put troops on a border. I can just have an information campaign.

This is a different type of conflict. You can’t even call it war, at least by international standards. We’re in a new era where we’re all trying to influence people. The only thing we have to guide us is international law that is 100 years old. No one anticipated the Geneva Convention would be applied to cyber warfare.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Switching gears – are you from a long line of engineers?

My dad was an electrical engineer, and Southern University recruited him to start an electrical engineering program. We’re a whole family of engineers.

One day at RAND, an older gentlemen came up to me and introduced himself as Percy Pierre. That was the greatest thrill of my life. Percy Pierre, the first African American electrical engineering PhD graduate, tutored my father in engineering at Notre Dame. I thought, if you don’t tutor my dad into becoming an engineer, a whole family of engineers isn’t created. And then my Dad created a whole generation of engineers teaching at Southern. It was a magical moment.

How did you decide on Michigan for your doctorate?

I was already working in southeast Michigan at General Motors, where I worked with Andrew Farah [BSE CE; MSE Electrical Science] in the electric vehicle program. I designed and developed integrated shifter and electronic ignition systems for the EV1. GM then sponsored my master’s degree at Berkeley.

At Berkeley, I worked with Pravin Varaiya, a very distinguished professor. One of Pravin’s students was Stéphane Lafortune, professor of electrical engineering and computer science at Michigan.

Pravin encouraged me to stay for the PhD, but since my fiancé was back in southeast Michigan, he connected me with Stéphane. That solidified my decision to try to get into Michigan.

What are some of your best memories from your time at Michigan?

Michigan treated me like family and took care of me. It gets emotional because they didn’t have to do that.

The whole story of my life started there. I quit my job and got married about a month and a half before my first day of class. I sold my car, bought a little three-cylinder Geo Metro and a house, and just said, “I’m going to go for it.”

When you dive into the deep end of a pool like that, and you don’t know a stroke, you’re just grateful that you didn’t drown. For a giant school like Michigan, it has an amazing ability to create a sense of belonging.

The great thing about Michigan isn’t that you have great football. The great thing about Michigan is that people find something to rally around.

Isaac Porche

What advice do you have for students?

It can be very valuable to pick a path, and stay with it. There are a lot of folks who will hop from job to job, and that can be very profitable. But if you follow a path and develop a lot of expertise, that is hard to recreate.

Why should students come to Michigan?

The great thing about Michigan isn’t that you have great football. The great thing about Michigan is that people find something to rally around.

People don’t go to the hockey games because the hockey team is great – the hockey team is great – but you find a family, because you can rally around that. There’s a reason why there’s a strong alumni following.

What is the value of an engineering degree?

It’s a very flexible degree. We snap up engineers at RAND because they can be quantitative. At a place like RAND that tries to be as quantitative as it can be, an engineering degree gives you credibility and respect.

You can take an engineer and develop them into almost any kind of professional, but it doesn’t necessarily go the other way around.

A degree in engineering doesn’t narrow your choices, it expands them.

MENU

MENU